Plant-based vanillin is produced from vanilla orchids, wood, rice or clove. Oil-based vanillin is derived from guaiacol made from crude oil. In this article you can learn more about how plant-based vanillin differs from the oil-based alternative.

1. What is vanilla?

The vanilla orchid, Vanilla planifolia, originates from Mexico. Spanish conquistadores brought cocoa and vanilla with them to Europe. Blended with sugar, it became a luxury drink in the 17th century. The plant expanded to the French colonies of The Bourbon Islands (Madagascar, Comoros, Reunion, Seychelles). Today, this is the region where most vanilla is produced. Vanilla pods are harvested in unripe condition and fermented through repeated exposure to sunlight and other natural processes. The brownish colour and vanilla flavour develops during this natural fermentation process.

Vanilla is rare, and it is the second most expensive spice after saffron, due to the extensive labour required to grow the vanilla seed pods. Pollinating is done by hand, and workers use a stick to move the pollen-coated part of the flower, called anther, towards the female part, called stigma. In its native habitat in Mexico, the Melipona bee pollinates the vanilla orchid. However, this process is sporadic at best, so hand pollination is also used in Mexico.

It takes 600 hand-pollinated blossoms to produce 1 kg of cured beans. Unripe beans are sold at local markets to collectors and curers who then sort, blanch, steam, and dry the beans in the sun. They are then sorted again, dried in the shade, and fermented. The beans are continually evaluated on their aroma and quality.

Today, Madagascar is the most recognised country for vanilla production, and more than 80% of the world's consumption originates here. Madagascar vanilla is well known for its quality and considered superior to vanilla produced in other regions such as Indonesia.

2. What does the vanilla market look like?

The worldwide demand for natural vanilla is substantially higher than the production capacity. We may categorise it as an underbalanced market, and it will remain so due to the limited potential for expanding production to new regions.

Global prices are high and subject to great fluctuations when weather phenomena like typhoons and tsunamis further limit production.

With an estimate of 18.000 products worldwide containing vanilla flavour, producers have to make use of natural vanilla supplements and alternatives.

The market can be divided into two distinct areas; the fragrance/cosmetics/personal care/home care industry and the food/flavour industry.

The fragrance industry mainly uses synthetic vanillin while food producers purchase the vast majority of the natural vanilla volume. To fill the gap between demand and supply, food producers also search for naturally produced vanilla flavours.

General scepticism towards synthetic additives and increased customer awareness combined with an increasing focus on natural ingredients are some of the main trends driving the market for natural substitutes for vanilla. In addition, sustainability has become a core focus of today's consumers who opt for products with the lowest possible environmental footprint. Consumers want ingredients produced without threatening biological diversity or using limited natural resources.

3. What is vanillin?

Natural vanilla extract is a mixture of several hundred different compounds in addition to vanillin. Due to the scarcity and cost of natural vanilla extract, the first commercial production of vanillin molecules began more than 100 years ago utilising the more readily available natural compounds such as wood and clove. Production of synthetic vanillin made from petroleum started as recently as the 1980s.

Though there are many compounds present in vanilla extracts, the compound vanillin (4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde) is primarily responsible for the characteristic flavour and smell of vanilla. Another minor component of vanilla essential oil is piperonal (heliotropin). Piperonal and other substances affect the odour of natural vanilla.

Vanillin is a crystalline phenolic aldehyde C8H8O3

Vanillin was first isolated from vanilla pods by Nicolas-Theodore Gobley in 1858. Until 1874 it was obtained from glycosides of pine tree sap, temporarily causing a depression in the natural vanilla industry.

Vanilla is a natural resource. The available volume and price highly depend on the annual global harvest, which usually amounts to about 2000 metric tonnes (mt). Vanillin constitutes only 2% of the cured vanilla beans' dry weight, which corresponds to 40-60 mt pure vanillin.

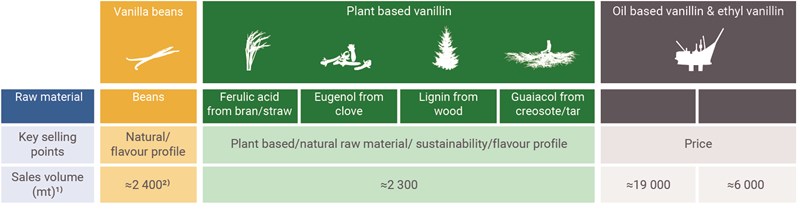

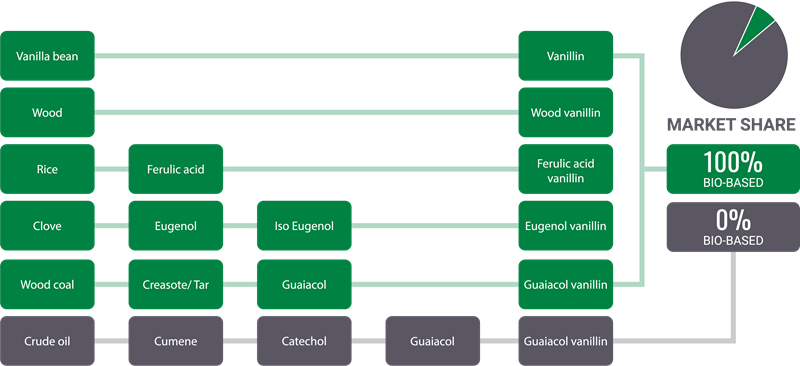

In addition to being obtained from vanilla, vanillin is manufactured industrially mostly by way of two main processes or routes. One uses plant materials to produce plant-based vanillin via various processes. The other uses crude oil, which is converted to vanillin (and ethyl vanillin) by a purely synthetic process.

The way to determine if a type of vanillin is natural or not is by analysing its carbon 14 (14C) content. The higher the 14C content, the more natural it is. You would expect a product from a natural source to be labelled 'natural'. However, there is no universal standard regarding what constitutes as a natural ingredient. Read more about this under "How to label products containing vanilla or vanillin".

When comparing vanillin from the vanilla orchid, plant-based vanillin, and vanillin from crude oil, there is no difference. It is the exact same molecule. However, when comparing the intensity of the flavour of these vanillin sources with an unbiased description, it has tremendous consequences for the vanillin users as it will determine the vanillin dosage in a formula. The illustration below shows the difference in intensity.

Vanillin intensity scale

4. What are the different types of vanillin?

As previously mentioned, the vanillin molecules are chemically the same irrespective of the source. However, based on which raw material it is produced from, there are three main vanillin flavour categories;

1. Vanilla

The term vanilla should only be used to describe flavour derived from the vanilla orchid. Its main application is food. Due to the limited production, vanilla stands for less than one percent of the vanilla flavour market worldwide.

2. Plant-based vanillin

Vanillin naturally occurs in many plants and is one of nature's protection systems. This protection comes in the form of inherent anti-microbial properties which take effect when the plants are attacked by fungi, yeast, bacteria, or insects. Many have tasted vanillin from wood when drinking wine matured in oak barrels. Vanillin from the oak in the barrels is extracted into the wine and gives it its round, but distinct vanilla character. The vanilla taste in the wine intensifies based on how fresh the wood of the barrel is and how long the wine is stored in the barrel.

Wood is a significant source of plant-based vanillin with rice and cloves being the other two.

The main application area for plant-based vanillin is food production. It fills the gap between the limited production of vanilla and the massive demand for plant-based alternatives.

3. Synthetic vanillin

Synthetic vanillin is a vanilla flavouring compound derived from the petrochemical precursor guaiacol. The main application areas are health care and cosmetics, but synthetic vanillin is also widely used in food production.

5. How to label products containing vanilla or vanillin

As established, the chemical compound vanillin is the main flavour component of cured vanilla beans. Vanillin can also be manufactured from other plants, with wood, rice, and cloves being the most significant. Finally, there is the chemically derived vanillin from crude oil.

While this assessment should pave the way for clear and balanced labelling practice, the reality is quite the opposite. Different regional governing bodies follow disparate procedures when deciding how vanilla flavoured products should be labelled.

For instance, vanillin from clove is considered natural in the US, but not in Europe. Vanillin from rice is considered natural in both Europe and in the US, while vanillin from wood is so far not regarded as natural in either region.

Let us look at the background for the strict labelling regulations. Throughout history, vanilla, due to its labour-intensive and limited production, has been subject to fraud and adulteration. Rules were established to protect the customer and enable a means of deciding the origin and quality of the vanilla flavour within a particular product. Additionally, the regulations aimed to create a fair competition environment where producers could not outprice their competitors by selling sub-standard products.

Although the objective is good, the various interests and policies make it hard to serve the consumers and help them make informed choices.

The vanilla bean is often considered to be the gold standard of vanilla flavour and one might expect top quality when presented with a product containing vanilla extract. In compliance with regulations, this is ground vanilla beans percolated with alcohol and water to create an extract.

The problem is that the quality of the feedstock used is unknown. Madagascar beans are considered to be of superior quality to beans from that of other regions. However, Madagascar beans also vary significantly in quality. Grade one is the top-notch relative to cuts which are the lowest with regards to vanillin content, aroma, and overall flavour.

Consequently, a consumer looking for vanilla extract has no means of knowing what bean quality is used in the extract.

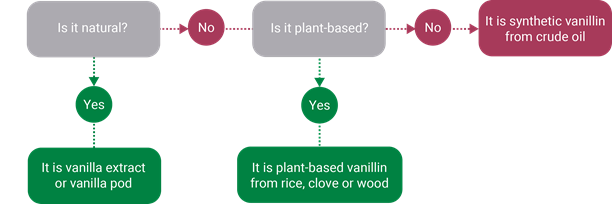

Consumers, manufacturers, and brands would benefit from a distinction between naturally sourced vanillin and synthetic vanillin when looking for a plant-based alternative to bean-derived vanilla flavours. To navigate in the confusing field of vanillin, one could simplify the subject through the following guide:

6. How sustainable is wood-based vanillin?

The rising demand for all-natural food and beverages and the similar scepticism for artificial additives among end-users, is the main driver for food producers wanting green replacements for their oil-based synthetic vanillin. The growing concern for climate change and biological diversity is also an important factor.

It is a widely believed misconception that vanillin from wood is manufactured via an environmentally harmful process using paper waste. At our biorefinery in Norway we use wood, more specifically Norway spruce, a renewable raw material sourced from forests managed in a proper, sustainable, and eco-friendly manner with short transport routes. Borregaard is Chain of Custody (CoC) certified following the FSC and PEFC forest certification standards. Norway operates one of the world's most sustainable forestries. For every tree that is harvested, a new one is planted. Today, Norway has three times as much forest as it did a hundred years ago. Every year the Norwegian forests, which have been meticulously monitored since the 1920s by the Land Resource Surveys, grow by 15 million cubic metres.

Deforestation is a threat to the climate and biological diversity, which could have put vanillin made from wood on the unwanted list. However, The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) considers wood-based products from sustainably managed forests to be part of the solution to the climate challenges the world is facing.

7. Which kind of vanillin has the lowest CO2 footprint?

Wood consists of 45% fibres and 25% sugar, which are the basis for specialty cellulose and bioethanol, respectively. Approximately 30% of the wood consists of binding materials from which vanillin is produced. From one kilo wood, Borregaard makes three grams of vanillin. Borregaard utilises 94% of the purchased wood, of which 82% turns into commercial products, 10% is used for internal energy and 2% is sold as bioenergy.

Consciousness around the negative effects oil production has on climate change puts pressure on manufacturers to look for more climate friendly production. Today, around 88% of vanilla flavourings come from synthetic vanillin derived from crude oil, 11,5% is plant-based vanillin, and 0,5% comes from the vanilla bean.

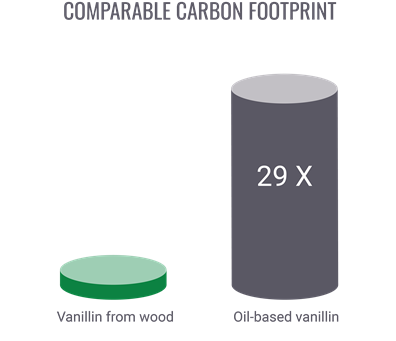

Changing to plant-based vanillin would be a sustainable alternative to oil-based vanillin, supporting customers wanting to consume responsibly in addition to meeting the demand for 'healthy/plant-based' options. Vanillin from wood has the lowest carbon footprint of any vanillin products on the market, arguably a key selling point for food producers and flavour and fragrance houses.

Borregaard operates the world's most advanced biorefinery. Using natural, renewable, and sustainable wood, helping the world move from oil-based carbon to green carbon from spruce trees. Our vanillin made from wood, EuroVanillin Supreme, is with its PEFC certification the only vanillin on the market with a sustainability certification, making it a uniquely sustainable choice.

8. Summary

Vanilla is among the world's most popular flavours. However, there are not enough vanilla orchids in the world to supply the increasing demand. Vanilla flavour from other sources fill the gap in an underbalanced market. However, with many definitions of what constitutes as natural, this makes it difficult to identify which vanilla flavours are natural and which are not.

Consumer trends are indisputable, and manufacturers try to adapt by labelling their products with "No Artificial Ingredients" or "All Natural". One of the most sought-after tastes in the world is indeed a natural ingredient when derived from the vanilla orchid's beans. We may have had an encounter with the real source ourselves, carefully carving out the flavour-intense content of a vanilla pod or using pure vanilla extract to really put the icing on the cake in our homemade crème brûlée or panna cotta.

In these situations, we should consider ourselves lucky, given the fact that vanilla flavour from beans represents less than one percent of the total supply of vanilla flavour in the world. There are, simply put, not enough vanilla orchids in the world to cover the demand, and there are limited areas where it is possible to crop and harvest these orchids.

Consequently, most sensory sensations from vanilla are due to flavour additives derived from other sources and typically applied to beverages, ice creams, chocolates, dairy products, and cosmetics.

If you are trying to grasp this subject's complexity, it might be wise to start by establishing three main pillars of understanding:

1. There is not, and never will be, enough vanilla orchids in the world to cover the demand for natural vanilla flavour.

2. Most vanilla flavours are from other sources than the vanilla orchid.

3. The non-natural vanilla sources can be natural (it might seem like a contradiction in terms, but it is not), or synthetic.